Managers don't always have the luxury of leading a homogeneous team. Between a newly recruited member of staff, an expert who has been autonomous for three years and a colleague who has lost motivation after a setback, you often have to deal with very different profiles... sometimes in the same day.

Situational management allows you to adjust your style without losing yourself in inconsistency. It's based on a simple principle: adapt your posture to the level of maturity and motivation of each employee. This model gives managers the flexibility they need to support, empower and develop their teams, without ever losing sight of the common direction.

Let's take two very concrete examples:

Managing these two profiles in the same way is bound to frustrate one of them. Adapting one's style is not a sign of weakness: it's a sign of managerial maturity, and a prerequisite for developing each person's skills.

There's nothing theoretical about this type of approach. It allows you to :

There's nothing theoretical about situational leadership. It's an agile management method that helps managers to support without suffocating, to let go without giving up, and to better allocate their time. By tailoring his support to real needs, he becomes more effective and fairer.

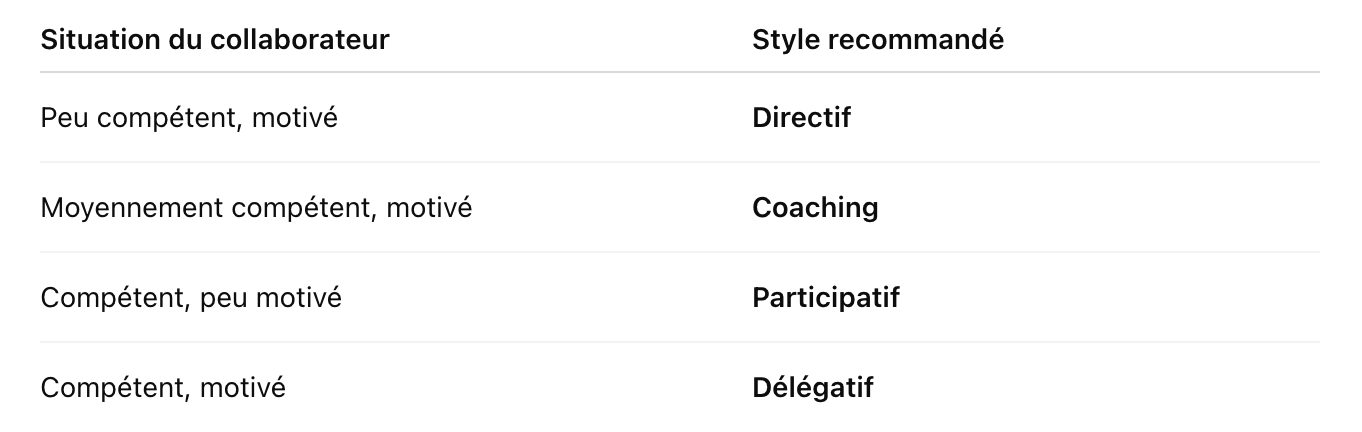

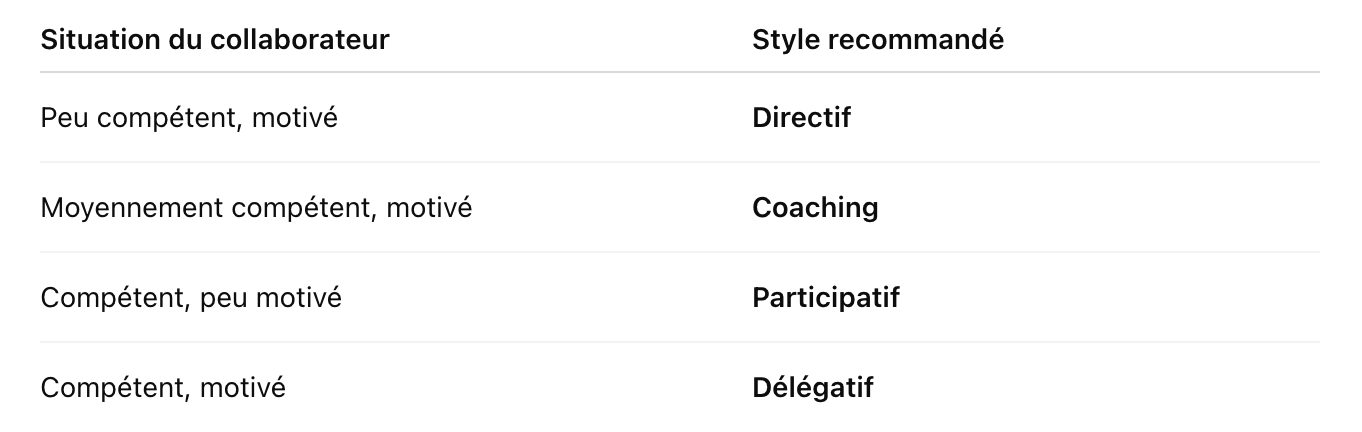

Situational management crosses two dimensions: the level of autonomy and the level of employee motivation. Four management styles emerge: directive, persuasive, participative and delegative. Each style corresponds to a different degree of support and initiative-taking.

Concrete examples:

These adjustments are not arbitrary: they directly support skills development and reinforce mutual trust.

This point is often misunderstood, even by experienced managers. It's not a question of "classifying" employees into fixed boxes. "He's a junior, so I remain directive" or "She's autonomous, so I don't worry about her anymore." That would be too rigid a reading of work dynamics.

An employee doesn't have a management style assigned for life. What counts is the context, the task, the level of pressure, and the expectations of the moment.

Let's take an example: Nadia, an experienced project manager, manages her usual portfolio perfectly. But when she's assigned to a strategic project with a high level of exposure to the Executive Committee, she has doubts, moves more slowly, and makes more demands. Coaching or increased participation may be useful during this period, before returning to a more delegative mode.

The coaching style must be adapted to the task, the moment and the employee's state of mind. And things can change quickly: in the space of a few weeks, the same person can go from needing a lot of supervision to being very autonomous... or vice versa.

The manager's real job is not to apply a recipe, but to make an ongoing diagnosis, taking the following elements into account:

In short, it's not a question of finding the right style for each person, but of adopting the type of leadership adapted to the situation, taking into account the level of maturity on a given subject.

Adapting your style is essential, but dangerous if done silently. A change in tone or level of involvement can be interpreted as a disavowal, a lack of confidence or a micro-sanction. And when nothing is said, employees fill in the blanks themselves, often with unflattering assumptions.

Example: "I'm more present on this subject because it's sensitive for the customer. My goal is for you to be autonomous on it within a month."

Saying what we do, and why we do it, defuses misunderstandings, avoids tension, and builds an adult relationship with the managerial posture. It also strengthens the relationship of trust, and clarifies the steps towards greater autonomy.

The best managers leave no doubt as to who decides what. They set clear rules, adapted to the context:

This clarity of decision-making allows everyone to know where they stand, and avoids interpretations. It can be formalized verbally, in an e-mail summary, or through a simple role sheet. It's not bureaucratic: it's reassuring.

Just because a manager adapts his level of involvement doesn't mean he's changing course. Objectives, priorities and quality criteria must remain stable. It is this stability that enables the team to find its bearings, even when the form of support varies from one person or subject to another.

A manager can switch from a directive to a delegative stance without calling into question the collective vision or expectations. What counts is consistency: "My support changes because the situation evolves, not because I change my mind". The implicit message: "My support adjusts, but our direction remains clear."

Situational management doesn't require 5 days' training. It's based on a simple understanding of situations and the ability to speak clearly about them. What makes the difference is not theory, but putting it into practice at the right moment, with the right words.

HR can :

These tools enable us to better support managers in their day-to-day decision-making, without drowning them in abstract models.

Some managers think they have to master everything to be credible. But knowing when to support, when to let go and when to come back is a sign of maturity, not hesitancy.

It is useful for managerial culture to value :

Situational leadership is neither an HR gimmick nor a fixed model. It's a practice that relies on listening, clarity and the ability to evolve one's coaching according to maturity, needs and context. The challenge is not to choose a style once and for all, but to keep a clear line in your objectives while remaining agile in your posture.

Managers don't always have the luxury of leading a homogeneous team. Between a newly recruited member of staff, an expert who has been autonomous for three years and a colleague who has lost motivation after a setback, you often have to deal with very different profiles... sometimes in the same day.

Situational management allows you to adjust your style without losing yourself in inconsistency. It's based on a simple principle: adapt your posture to the level of maturity and motivation of each employee. This model gives managers the flexibility they need to support, empower and develop their teams, without ever losing sight of the common direction.

Let's take two very concrete examples:

Managing these two profiles in the same way is bound to frustrate one of them. Adapting one's style is not a sign of weakness: it's a sign of managerial maturity, and a prerequisite for developing each person's skills.

There's nothing theoretical about this type of approach. It allows you to :

There's nothing theoretical about situational leadership. It's an agile management method that helps managers to support without suffocating, to let go without giving up, and to better allocate their time. By tailoring his support to real needs, he becomes more effective and fairer.

Situational management crosses two dimensions: the level of autonomy and the level of employee motivation. Four management styles emerge: directive, persuasive, participative and delegative. Each style corresponds to a different degree of support and initiative-taking.

Concrete examples:

These adjustments are not arbitrary: they directly support skills development and reinforce mutual trust.

This point is often misunderstood, even by experienced managers. It's not a question of "classifying" employees into fixed boxes. "He's a junior, so I remain directive" or "She's autonomous, so I don't worry about her anymore." That would be too rigid a reading of work dynamics.

An employee doesn't have a management style assigned for life. What counts is the context, the task, the level of pressure, and the expectations of the moment.

Let's take an example: Nadia, an experienced project manager, manages her usual portfolio perfectly. But when she's assigned to a strategic project with a high level of exposure to the Executive Committee, she has doubts, moves more slowly, and makes more demands. Coaching or increased participation may be useful during this period, before returning to a more delegative mode.

The coaching style must be adapted to the task, the moment and the employee's state of mind. And things can change quickly: in the space of a few weeks, the same person can go from needing a lot of supervision to being very autonomous... or vice versa.

The manager's real job is not to apply a recipe, but to make an ongoing diagnosis, taking the following elements into account:

In short, it's not a question of finding the right style for each person, but of adopting the type of leadership adapted to the situation, taking into account the level of maturity on a given subject.

Adapting your style is essential, but dangerous if done silently. A change in tone or level of involvement can be interpreted as a disavowal, a lack of confidence or a micro-sanction. And when nothing is said, employees fill in the blanks themselves, often with unflattering assumptions.

Example: "I'm more present on this subject because it's sensitive for the customer. My goal is for you to be autonomous on it within a month."

Saying what we do, and why we do it, defuses misunderstandings, avoids tension, and builds an adult relationship with the managerial posture. It also strengthens the relationship of trust, and clarifies the steps towards greater autonomy.

The best managers leave no doubt as to who decides what. They set clear rules, adapted to the context:

This clarity of decision-making allows everyone to know where they stand, and avoids interpretations. It can be formalized verbally, in an e-mail summary, or through a simple role sheet. It's not bureaucratic: it's reassuring.

Just because a manager adapts his level of involvement doesn't mean he's changing course. Objectives, priorities and quality criteria must remain stable. It is this stability that enables the team to find its bearings, even when the form of support varies from one person or subject to another.

A manager can switch from a directive to a delegative stance without calling into question the collective vision or expectations. What counts is consistency: "My support changes because the situation evolves, not because I change my mind". The implicit message: "My support adjusts, but our direction remains clear."

Situational management doesn't require 5 days' training. It's based on a simple understanding of situations and the ability to speak clearly about them. What makes the difference is not theory, but putting it into practice at the right moment, with the right words.

HR can :

These tools enable us to better support managers in their day-to-day decision-making, without drowning them in abstract models.

Some managers think they have to master everything to be credible. But knowing when to support, when to let go and when to come back is a sign of maturity, not hesitancy.

It is useful for managerial culture to value :

Situational leadership is neither an HR gimmick nor a fixed model. It's a practice that relies on listening, clarity and the ability to evolve one's coaching according to maturity, needs and context. The challenge is not to choose a style once and for all, but to keep a clear line in your objectives while remaining agile in your posture.

Situational leadership is a management model that involves adapting one's style to the skill level and motivation of an employee. It is based on four types of leadership: directive, coaching, participative and delegative.

To apply situational management, a manager needs to assess the level of maturity of each team member, then adjust his or her support: give more guidance to an employee in a learning phase, or delegate completely to an autonomous profile.

Adapting your style allows you to provide the right level of support without losing consistency. By making the rules of the game and decision-making clear, the manager reinforces understanding, trust and the development of skills within the team.

Discover all our courses and workshops to address the most critical management and leadership challenges.